Photo essay: Growing coffee, sowing peace in Colombia

Date: 07 August 2018

For Cielo Gomez, every day is work day, starting with coffee 5:30 am. A mother of three, a wife, and now a coffee grower with her own land, it’s a labour of love.

Gomez and her family live in the municipality of El Tablón de Gómez, in the southeast of Nariño territory, Colombia. The municipality is known for its coffee and scarred by decades of conflict between the Colombian guerillas, army and the paramilitary forces. Its most recent claim to fame is successful land restitution to farmers, with 562 families being part of the programme and 198 restitution sentences implemented since 2013.

More than 7 million people in Colombia were displaced by the armed conflict since 1985, and some 8.3 million hectares of land was illegally occupied. The final peace agreement between the Colombian Government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) was signed in 2016, ending more than 50 years of conflict.

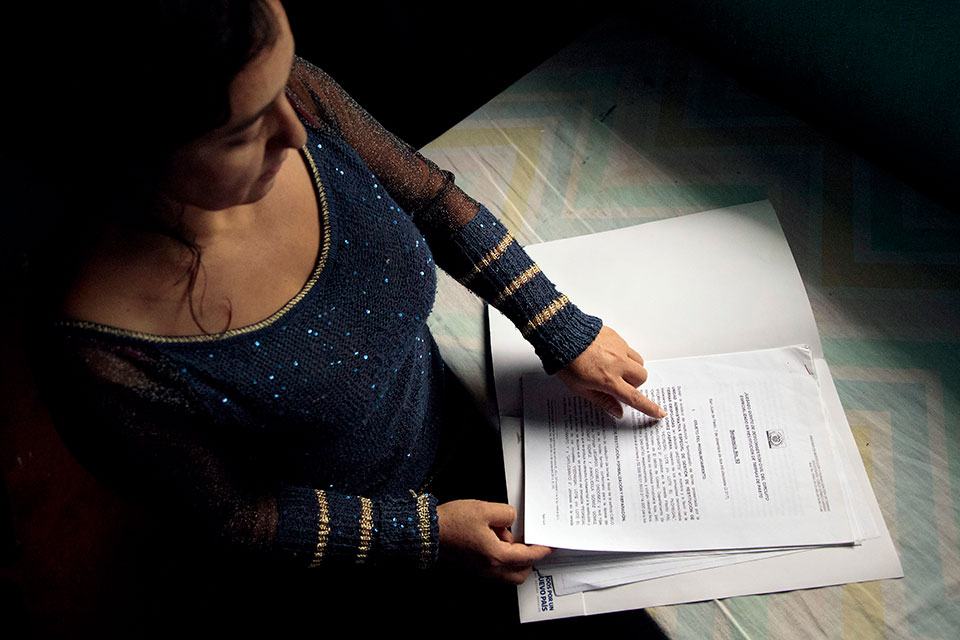

The Victims and Land Restitution Law (Law 1448) aims to return illegally acquired land to its rightful occupants. In many cases, the land restitution process formalized the ownership of land for those who had already returned to their land but did not have formal documents to prove ownership.

“In April 2003, there was a conflict between the guerillas and the army. We were all afraid. A child was killed in the cross fire in La Victoria. The military went to every house, looking for the guerillas and threw out our things—mattresses, clothes, everything…” recalls Cielo Gomez. “I was in my in-law’s house when the military came to our house. The guerillas had put bombs on the route between my home and my in-law’s home, so the military couldn’t reach us.”

Cielo’s story is echoed by many others in the area. There was mass exodus of people, trying to escape the escalating violence, having to leave their homes, land and any possessions that they couldn’t physically carry with them. The Gomez family were among those who decided to come back after a month in hiding, as they had nowhere else to go.

“When we returned, we found that the roof of our house was destroyed, there was no electricity…The army said they had killed and buried the guerillas in mass graves.”

Cielo and her family got their land back as part of the land restitution process initiated by the Government of Colombia. But at first the land was only in her husband’s name.

Through a UN Women project implemented by Corporation for the Social, technological and economic development of Colombia (CORPDESARROLLO), funded by the Government of Sweden, Cielo learned about her right to land, developed leadership and business skills.

“There were three lots of land, and now I own one of them, and the other two are under my husband’s name. We grow coffee in all three lots. Both of us are now land owners and that’s economic autonomy,” says a proud Cielo.

Since then, she has taken a loan from the bank and bought another piece of land.

“I have 10,000 bushes of coffee now. I used to think before that women can plant and grow coffee and harvest, but not trade it,” she says, adding that she asked her husband to help with planting the coffee. “It will be a 50-50 partnership, I told him, and we would both benefit from selling the coffee.”

Cielo can now afford to hire 10 workers to work her land. For Deyanira Cordoba, a young woman from the same project, visiting Cielo, coffee-growing runs in the family across generations. “My dream is to become a coffee entrepreneur and help my parents and my community,” says Deyanira. “It’s not just men who can do business. We women can make and achieve our own goals.” Read Deyanira’s story>

The project also worked with men and discussed masculinity issues with them. “My husband understood that women work all the time, even on Sundays, while men have rest at home. He understood that women have the right to rest as well. Now he shares some of the chores at home. He washes his own dishes and feeds the animals,” says Cielo.

Oneda Alban, 40 years old, from the village of La Victoria, has a very similar story. She is the first woman in her family to ever own land, although she had grown coffee all her life.Not only did the project make her aware of her rights, it had a tremendous impact on her relationship with her husband.

“My husband went for the masculinity training,” explained Oneda. “In the second workshop that my husband attended, they gave him this little pot and asked him to throw it and to think of a person he loved.” For Oneda’s husband, the pot represented Oneda, and how violence impacted her.

“My husband put the pot back together and wrote my name on it. He came home and said, ‘I have a surprise for you.’ He gave me the pot. He had never before brought me a gift! Since that day, we started talking to each other like a couple. We are teaching our boys to treat women with respect.”

Growing coffee is hard work. Often, small farmers like Cielo, Oneda and Lucia don’t make nearly enough for their products. That’s where 27-year-old Joana Gomez, Coordinator of the Trading Team at the association of coffee growers (ASOPRO Café) in Tablón de Gómez wants to make a difference. She is the only woman in the trading team and joined UN Women’s project in 2017.

“I love coffee and knowing everything about coffee, but also where it goes,” she says. “The coffee growers do all the work, but make minimum amount of money. Most of the benefit goes to the intermediaries who trade the coffee.”

The Association takes away the middlemen in coffee trading so that the farmers can bring their beans, roast them and trade them directly.Currently, the association can produce a maximum of 1,000 pounds of coffee in a year. A complementary project by FAO is teaching the members sustainable agricultural practices as well as tasting skills, so that they can roast different varieties of coffee.

“We are applying for quality standard record, barcode and permit from the national coffee federation. Without this permit, we cannot produce more and cannot trade internationally,” explains Joana Gomez.

“My dream is to export this coffee internationally, so that people know the excellent quality of our coffee. Anyone who has tasted this coffee is charmed by its taste, You won’t find another coffee like this in Colombia.”

Two years after the historic peace agreement that formally ended five decades of conflict between the Government of Colombia and Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), peace is intimately linked with economic empowerment, justice and decent life. For the coffee-growing women of Tablón de Gómez, life is safer, at last. Now they are working to make their lives better, growing coffee and sowing peace.